--------------------------------------

Item 1

Final Wakes Week marks end of an era

By Chris Gorman

WEST Craven's schools will empty today (Friday) for nine weeks as pupils

embark on a marathon summer holiday.

And families across the district will take advantage of "cheap holidays"

in off peak periods for the last time.

The next school year will not begin until Monday, September 4, as the

area's school holidays comes into line with the rest of the country.

advertisement

The move which met with widespread opposition from parents, teachers and

councillors will mean the end of the traditional Wakes Week, which

characterised East Lancashire's mill towns.

The area's schools traditionally broke up almost a month before others in

the county and returned to classes in early August, before taking a

half-term holiday in mid-September.

The custom stems from the 19th century, when mill owners in a town or

district would all stop production at the same time to give their workers

a holiday.

Many shops would close and the streets would be almost deserted as

families left for the seaside, but the custom carried through to modern

times.

In 2003, the Herald reported that retail trade still halved in the area

during "Barlick fortnight".

Objections to the standardisation of school holidays and term dates across

the 11 education districts of Lancashire centre around the loss of cheap,

"off-peak", early July holidays for families, which, it is feared, could

also cause higher absence rates as parents took their children out of school.

Concerns have also been raised that the extended break will lead to

increased juvenile nuisance problems, which police have made efforts to address with diversionary activities, and difficulties for youngsters returning to education after a long period of abstinence.

A last ditch attempt to prevent the ending of Wakes Week was made by

opposition councillors, including Barnoldswick representative David Whipp,

but the move was forced through by Lancashire County Council's ruling

Labour group last June.

Some East Lancashire factories will change the dates of their summer

shutdown to fit in with the new term times.

7:10am Friday 30th June 2006

----------------------------------------------------

Item 2

During Lancashire's industrial era, the most widely anticipated time of

the year was the annual summer holiday, generally known as the Wakes Week.

The origin of the wakes are to a certain extent still shrouded in mystery,

although it seems likely that they were originally intended to commemorate

the anniversary of a church or chapel being founded in the local area.

However, by the 19th century, the wakes had few religious connotations,

although 'rush-bearing' processions to the local church continued in some

parishes for many decades.

The Lancashire wakes are best seen as a tradition which became an

institution. Each town in the cotton belt had celebrated the wakes in one

form or another for centuries before the industrial revolution. Once

their lives were regimented by the mill clock, most factory workers felt

even more strongly that this traditional 'time-off' should be preserved

and formalised.

Each town had its own insular tradition, which eventually developed into

a 'week off work' - consequently, local towns took their weeks at different

times to one another. The owners of mills and factories found that they

could do little to prevent their workers from taking the wakes week off -

they would simply not turn up for work. Millowners could hardly complain,

as they were not overly-generous with holiday entitlement.

Nick Harling

-----------------------------------

Item 3

Christmas, Easter and Whitsun together with saints' days, especially the

patronal festival of the parish church, provided the annual holidays.

Many of these survived the Elizabethan and Cromwellian reformations.

The very word holiday of course originates from Holy Day. Boxing Day,

Easter Monday and Whit-Monday were 'holidays' following the respective

major festivals; and Wakes Week followed the celebration of the feast of

the church's patron saint. Added to these later were the religious

observances associated with agricultural crops: Rogation Days and Harvest

Thanksgiving - times of prayer for, and thanksgivings after, a season

of successful crops.

----------------------------------

Item 4

Historic sports: Bull-baiting was a popular fair sport

Today, wakes are annual fun events, often in aid of charity. But that

was not always the case, as Carol Malkin discovered.

MANY Derbyshire villagers still refer to their annual summer fete as

the "wakes", an organised week of events, competitions and sports that

usually culminate in a carnival.

The original wake or "watch" was a night of solemn prayer. It was held

on the anniversary of the death of the saint to which the parish church

was dedicated or, failing that, the Sunday immediately afterwards.

The next day families would get together, have a feast and play games.

Later, villages decided to hold fairs at wakes and many applied for

both weekly markets and a two or three-day fair on their saint's feast day.

One of Derbyshire's earliest granted market charters was for Hartington

in 1203, which allowed villagers to have a regular Wednesday market and a

three-day fair at the Feast of St Giles.

The week previous to wakes was a time for preparation. It involved cleaning

the house right through, sometimes even giving it a whitewash.

Then, the entire family would be treated to new outfits. For children the

moment of excitement was when the fair arrived. They couldn't wait to

spend their money on the coconut shies and hoop-la. In Hathersage they

had Fair Day Friday with stalls that sold gingerbread, nuts, brandy snaps

and a flat brown and cream humbug-type sweet called "Marry Me Quick".

The fair at Staveley Feast used to be held on the recreation ground. In

those days people paid to see freak shows featuring bearded ladies and

two-headed calves. There was also a boxing booth where the local men

could pitch themselves against the fairground lads to try to win £5.

Staveley's modern day feast celebrations include re-enactments, charity

fun runs, demonstrations by Whirling Dervishes and the funfair now held

in the town centre.

Another fair within living memory belonged to Tim Ray. Every summer he'd

travel around Derbyshire and set up at any village which was holding its

wakes or well-dressings.

One of his regular stops would be opposite the Miner's Standard at Winster.

Children would squander their pocket money to try to win a penny whistle

or a peashooter.

But Tim Ray's fair was best known for a ride called the High Park

Swingboats.

One of the biggest fairs in the county is the Ilkeston Charter Fair.

When it was first granted by Henry III in 1252, it was held in August

at the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

It was moved to October in 1888 to amalgamate the wakes, statute

(employee hiring) fair and end of harvest celebrations.

Entertainments and sideshows during the 19th century included illusion

booths, theatres, waxworks, freak shows and a travelling zoo or "beast show"

with snake-charmers and dancing bears.

By the 1890s there was also a set of steam-powered gallopers.

As well as the drinking, feasting and general revelry, villagers at wakes

also held their own games and amusements. Gurning through a horse's

collar, tug-of-war, eating scalding hot puddings and racing naked

through the streets, albeit daft, were harmless fun.

However, other events, although referred to as sports, were bloodthirsty

and barbaric. For example, an early event was to hoist up a live goose

on a piece of rope so that riders could gallop underneath it and try to

pull its head off.

Baiting animals had been popular since medieval times and bull-baiting

was the most common. The bull would usually be fired up by having pepper

blown up his nose. Then he was tied up to a bull ring and set upon by dogs.

Folk would bet on which dog would succeed in pinning the bull down by

its nose. In 1820 at Bradwell wakes, a man called Frank Bagshaw tied

himself to the bull's tail to hold it still. When the bull saw the dogs

being brought out it took off dragging Bagshaw through the village brook.

Bull-baiting was banned in 1835, although Bonsall had put a stop to theirs

by 1811. But, in 1834, the rector at Bonsall, the Rev Robert Greville,

caught a group of 40 men and dogs with a bull during the wakes week.

The vicar protested against their brutal amusements and managed to save

the bull by purchasing it from them for one guinea.

A bull ring is still kept in Bonsall church but opinions differ as to

whether it is from that particular incident. Three other bull rings can

be found around Derbyshire.

At Foolow, near Eyam, there is one on the village green just in front of

the ancient cross. There's another in Eyam just outside the Peak Pantry

cafe in the market square. It used to be buried underneath the square

itself until the Rev Francis Shaw had it uncovered in 1911.

People still had to crouch down to get a look at it then as, although

visible, it was covered by an iron grille. It wasn't until 1986 when

the square was altered that the bull ring was raised and put in a

more convenient place.

Finally, there is still a bull ring at Snitterton, near Matlock, and,

since 1906, it has been preserved by the Derbyshire Archaeological Society.

Bull-baiting wasn't only used as sport; people believed that it tenderised

the tough meat of the bull and at one time a bye-law stated that every

butcher in Chesterfield should have all bulls baited before being

slaughtered.

If not, they could risk paying a 3s 4d fine.

Bulls weren't the only animals to suffer. Bears were also subjected to

being brutalised by dogs. In John Farey's Customs Observed In 1817, it

was noted that, in June 1810, a young bear in Buxton was being tortured

by dogs on a daily basis.

Later that same year, a man called John Smith was tried at Chesterfield

and sent to prison for being a "vagabond bearward". He'd been travelling

around, putting on bear-baiting shows and collecting money from spectators.

Thankfully bear-baiting was abolished at the same time as bull-baiting.

Cock fighting wasn't banned until 14 years later. Birds that regularly

won were worth a lot of money but any that refused to fight back would

be killed on the spot. Some great matches were so memorable that people

wrote songs about them.

One originally written in 1715 was called The Hathersage Cocking but over

time has lost its original local theme.

By Victorian times, as seaside holidays and commercialised sport became

fashionable, wakes were no longer the high point of the year.

Village populations were starting to decline which made events harder to

support. The First and Second World Wars also put the dampers on wakes

as people felt selfish having a good time while others were laying down

their lives for their country.

However, more recent years have seen villages making an effort to keep

their wakes celebrations with parades, stalls, charity events, scarecrow

competitions and rural demonstrations.

Some use the wakes to keep their local traditions alive.

Morris dancing has been used as an entertainment at wakes since it

became established in England in the 17th century and it was first

recorded in Derbyshire at Tideswell in 1797.

By 1863, the Winster Morris Dancers were entertaining crowds with their

unique dances exclusive to the village.

Another ancient custom is guisering where people dressed up, blackened

their faces and went round the village asking for food and money. This

was historically done during festive times but Tideswell now has a group

of Tidza Guisers who perform for the crowds at wakes.

They include a traditional mummers' play called Tidza Saw Y'eds which

tells of a farmer whose cow gets its head stuck in a gate. He tries to

solve the problem by sawing off the cow's head but then a doctor comes

along, sews the cow's head back on and she miraculously comes back to life.

The play itself isn't practised much, the emphasis being on the elaborate

costumes. But it is performed about three times during the week and also

at Litton on the Tuesday as both villages share the same wakes week,

around John The Baptist's day.

All the money collected during the plays goes towards Tideswell Wakes.

Eyam's sheep roasts have been traditional for many years and the current

revolving roasting jack, was erected to mark the Festival of Britain in 1951.

Every carnival day, it roasts lamb from around 10.30am. When not in use,

it stands displaying the date when the next sheep roast will be held and

inviting all visitors to "come and see an old Eyam custom".

In 1536, an Act of Convocation tried to move all wakes celebrations to

All Saint's Day to reduce the amount of holidays people were taking.

But people refused to stop celebrating on their own saint's day.

Nowadays, villages still stick to the same week every year and, in the

case of Derbyshire, often tie their wakes in with the local well-dressings.

-----------------------------------------

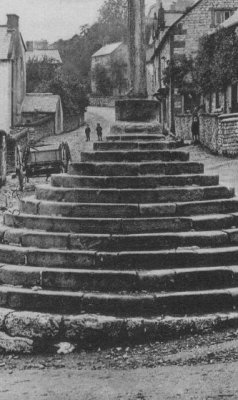

Click on photo for enlargement (on CD only)

Have any more information about this photo?

Please e-mail the author on:

Click on photo for enlargement (on CD only)

Have any more information about this photo?

Please e-mail the author on:

Click on photo for enlargement (on CD only)

Have any more information about this photo?

Please e-mail the author on:

Click on photo for enlargement (on CD only)

Have any more information about this photo?

Please e-mail the author on: