- I may never learn just what kind of day it was, probably not snowing or freezing, but, just how was it? Sunny, hot, humid or dull, rainy and overcast?

-

I know the date, but how did the day seem to the people who were involved in that commonplace, but to them and me, unique occurrence?

-

That day as far as I know has no place in my memory banks, yet I was there, I have no reason to doubt that I was there, that mid-morning of 29th June 1926. If I researched the local papers for that area and time I may find some reference to the weather.

-

I’ve never really thought about it until now. It is, of course, academic, but it would be satisfying to know. I was told it was a Tuesday and a check on the perpetual calendar confirms it was a Tuesday.

-

Neither am I sure of the location of the event, I’ve never seen it written down and since I have no personal knowledge of the event, it would follow that I have no personal memory of the location, that is, I know the area but the exact address I do not know for certain.

-

I recall that I was told that 29 John Street Normanton, West Yorkshire was the place, but I need it confirmed by documents yet to be seen.

-

Mother would have known of course but she passed on some years ago now, Dad died whilst I was a boy of eight.

-

Mum and Dad would be the two people who would be sure of the time and place, for now it must suffice that 29 John Street, Normanton, West Yorkshire and Tuesday the 29th June 1926 describes the place and time on which I was born, a healthy 81/2 pounds, the fifth child of Mathew O’Shaughnessy and Alice, nee Woodcock.

-

My parents were not wealthy and came from working class stock of miners and railway workers, so for all their children a ‘short’ birth certificate had to suffice. Hence the lack of information mentioned earlier. I do not think any of us ever had a full certificate.

-

My paternal great grandfather John Shaughnessy came to England with his wife Catherine (nee Malley) and one child Peter in the aftermath of the terrible Irish Famines of the 1840’s. They came from Westport, Co Mayo and Peter is listed as having been born there about 1847. As Honor the next child was born at Willenhall in Staffordshire in 1850, the immigration must have been within the three years from 1847-1850.

-

On the 1851 Census he (John) was found to be living at Portobello, Willenhall in Staffordshire. He was an iron ore miner but was a potato farmer in Mayo.

-

They had six children, Peter 1847 Co Mayo. Honor 1850 Mary 1856, and Mathew 1859 Margaret 1861, and Annie 1862 born in Portobello Willenhall. By 1881 Census, Mathew was in Yorkshire and Peter was in Kent, but parents John and Catherine were still in Willenhall. They did eventually move to West Yorkshire and As far as I am yet aware they lived for many years in Wakefield Road Normanton but Streethouses has been mentioned. John’s son Mathew, my grandfather, married Hannah Mary White on 14 May 1883 at Halliwells Chapel, Tanshelf, Pontefract, Yorkshire. They had 10 children, of whom the fourth, Mathew, born 1893 was my father.

-

During this period of time another family was developing in Kidsgrove, Staffordshire, about 40 miles north of Portobello, in the area broadly known as the Potteries. It was also a thriving mining area. The Woodcocks were well established.

-

Enoch Woodcock was my maternal great grandfather and he married Dinah (maiden name not yet found) and raised a family of eight. George, the fourth child, was my grandfather born 1871. Granddad was shown on the 1871 census as being three months old and born at Kidsgrove but the census address was Smallthorne, so the family moved during the first three months of 1871, about six miles further south east to Smallthorne, the reason not known for sure but as usual it would have been purely economic, either for work or better wages.

-

1893 saw the marriage of my grandfather to Harriett Ball at St Saviours Church in Smallthorne on Monday the 28th August. There were nine children born to this marriage, My mother Alice was the first born in 1897 on 4 April at Smallthorne. For years we understood her birthday to be 22 April, but a copy of her baptismal certificate corrected us to 4 April. She was baptised on the 12 May 1897, a maximum of six weeks after she was born so the 4th of April is not likely to be a mistake. (42 days was the time limit for registration). Also her marriage certificate gives her age as 21 on her marriage date of 10 April 1918.

-

Mother spent practically all of her childhood at Smallthorne and although the precise date is not yet established it would appear likely that shortly before the outbreak of World War 1 the family moved to Normanton in West Yorkshire to 23 West View.

-

Father to be and his parents were already living at 28 Lower Station Road, Normanton. Both were terraced houses, 28 being the end of a terrace and 23 the second end and they were back to back with a narrow cobbled lane between the two.

-

Normanton at this time had quite a number of coal mines and due to the way the various railway companies emerged and developed it was, for a small place, quite an important junction and had been so since the very early days of railways. The station platforms were far longer than the size of Normanton warranted and could accommodate the longest expresses of those early days and much later years.

-

There were fairly extensive sidings for rolling stock and a thriving locomotive depot for servicing. Coupled with the need to transport coal and passengers it must have been a thriving area but whether the benefits were reflected towards the work force or not is not within the scope of this narrative.

-

Mathew O’Shaughnessy and Alice Woodcock were married on the 10 April 1918 at St Johns RC Church, Newlands Lane, Normanton. Their children were Walter, March 1919. Nellie, March 1921. Kenneth, December 1922, Colin, May 1924, myself George, June 1926 all born at Normanton. Eileen, was born seven years later at Wirksworth in Derbyshire, October 1933

-

In 1926, the year I was born there was labour unrest (no pun intended) and it resulted in the General Strike, this subsequently collapsed and resulted in economic problems which lasted for many years. It appears that as one result, my father was requested by the London, Midland and Scottish Railway Company, by whom he was employed to relocate from Normanton to Cromford in Derbyshire. There in 1927 or 1928 he took up his employment on the Cromford and High Peak Railway. This was a unique company first authorised in 1823, later incorporated into the London and North Western Railway and latterly a part of the London Midland and Scottish Railway at amalgamation in 1923. It traversed a difficult route using steam powered cable and pulley inclines and steam engines across some of the higher areas of the southern Pennine hills of mid Derbyshire. Dad was employed as a stationary Boiler Fireman which operated the first of these inclines , that at Sheep Pasture top at Cromford.

|

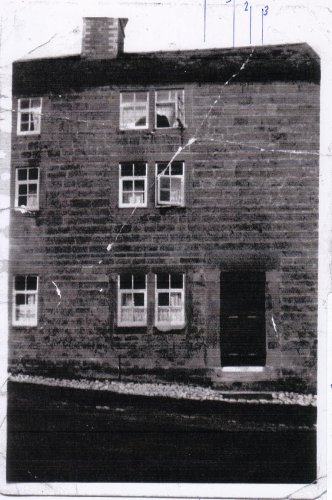

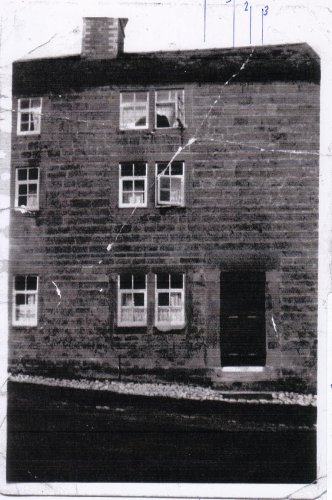

Then 54 (now 142) The Hill, Cromford. Taken 1930-35

|

Whilst I was born in June of 1926 I remember nothing of my early time at Normanton and my first memories are of Cromford. I must have been around two years old when the rest of the family moved to Cromford. Dad had arrived some time earlier and was in lodgings with an elderly couple, Mr and Mrs Marples of Rise End Middleton. My first recollections were of our house at Addison Square half way up the main part of Cromford Hill on the route to Wirksworth. It was, I believe, a council house of fairly recent construction and had a reasonable amount of garden for the area. We were destined not to occupy that house for long and within months we had moved to No 54 The Hill.Cromford, only a hundred yards or so higher up the hill.

It was cheaper and although may not have been as large as the earlier house, it was three storied and possibly had the odd room extra which was more suited to a large family. There was no running water laid on, lighting was by gas and cooking had to be done over a coal fired range which had an oven and a tank for heating water on the opposite side to the oven. There was a drain but no toilet sanitation except for the outside closet at the bottom of the small yard. Cold water was only available from a tap across the road from the house. In the small ‘kitchen’ there was a large half circle copper under which a fire had to be lit every Monday morning as washing was not done on any other day in those times, water was carried across the road and then all the clothes were boiled. It was quite a ritual for a small boy, then the drying and ironing had to be done.

-

From lodging with Mr and Mrs Marples for a relatively short while a friendship developed which spread to the family and lasted . I remember Mr Marples (Tom) as a slightly built man and his wife (Sally) was more robustly built. I do not know how old they were but to a three year old they were ancient! We visited them several times and I do not recall objecting..

-

My memories of the house and garden at Addison Square are rather scanty, I do not recall anything of the upstairs at all. My main memories are of standing, with mother, by the open front door which looked out over the valley and watching the rain and lightning of a thunderstorm. Another occasion was helping in my way to strip wallpaper ready for redecoration.

-

I started school in 1931 at Arkwrights School in North Street, my elder three brothers and one sister were already attending. For the next four years until I reached nine life seemed (in retrospect) to take on a routine which was happy enough and calm, school, evening and weekend playing, Sunday was an important day in our lives, being Roman Catholics the nearest church was at Gorsey Bank at Wirksworth about two and a half miles away, with Mass in the morning, catechism in the afternoon and possibly Benediction in the evening, fifteen miles could be walked, and at that age and having four older and stronger siblings I sometimes felt the strain. The walk was fine but maybe the real strain was spending up to an hour in church each time. At that age I cannot say that I really enjoyed Sundays. I repeat the walk was fine but being the youngest and smallest the pressure was upon me to keep up and children do not take prisoners.

-

Money was very tight in those days, not only with our family but with many families, much of our entertainment was home made in the immediate area in which we lived. It was really ideal for children to grow up in an area like that..

-

Cromford nestled in the bottom of the valley and spread half way up the hill towards Wirksworth. The valley was the River Derwent’s path from the North West to the South East of Derbyshire and as with many valleys was subject to flooding so most of the early roads or tracks tended to cross valleys from high ground to high ground, in this case from Wirksworth down Cromford Hill to the river (hence possibly the ford in Cromford) then climb the opposite side to Starkholmes and thence to Matlock Any flat portions of the valley were on the southwestern side of the river so settlement would tend to be there also and so the village developed up the hill towards Wirksworth.

-

Our playground was therefore mostly on the side of the hill with hardly a level portion anywhere, contour following excepted, and must have contributed to all the inhabitants stamina.

-

The whole area was particularly attractive. The river flowed from North West to South East as already mentioned, the railway closely followed the river’s line, there was a main road running northwards to Matlock through a narrow gap blasted through the limestone early in the nineteenth century, then from Cromford Market Place two roads went south, one on each side of the river, the east side one being much the older.

-

During the seventeen hundreds a canal was commenced at Cromford that ran south to Ambergate, then turned east towards Ripley and the Nottinghamshire border. Bonsall brook which was used for powering Arkwright’s first mill was dammed and formed a substantial lake behind the Greyhound Hotel on the market place, serious fishing for minnows was done there. A swan or two were usually in residence along with other members of our feathered friends.

-

There were fields in plenty, trees to climb, blackberries, wild strawberries, hazel nuts, crab apples and wild flowers in profusion. There were farms where we were tolerated and spent many enjoyable hours in the lofts and sheds, sometimes in return for a little light work in the way of collecting eggs from the chickens which, in that era, were always free range, or chopping mangolds for cattle feed. Haymaking was a time when any extra labour was always welcome, with potent ginger beer in abundance. Much of the hillside in that area was mined many years ago for lead, and were topped out mainly with a covering of stones, but we were made aware of the dangers as most of the shafts had not been filled in. The canal and Cromford meadows were another popular play area, the canal was very little used at that time and fish and frogs, water voles and bird life quite plentiful. There were lots of paths and due to the topography of the area the views constantly changed through the next dip and over the next rise, boring it was not! Where dad worked at the engine house at the top of Sheep Pasture incline was always a popular place to visit, and we were tolerated there, it was interesting and the static water ponds for the engines generally had newts for us to catch. Imagine wandering around an operating railway area today, even though this was much more sedate and controllable.

-

I was once allowed to ride down and up the incline in a goods wagon as dad operated the winding engine and on another occasion I was lucky enough to be allowed a ride on the footplate of an engine from Sheep Pasture top along to the arch at Steeple Grange, I had to walk back though, but even if I had lived at Waterloo station or Clapham Junction, being allowed on the lines, let alone being able to board any stock would have been a dream, but at that stage of my life even Derby was a place far away in the mists and I don’t think I had even heard of London.

-

There was and still is, a fine panoramic view from the top of Sheep Pasture and an even finer one from the nearby Black Rocks, although quarrying has brought it’s share of environmental pollution with sight, sound, dust and heavy vehicles on road which are recognisably hazardous. Our main play area, a valley at the rear of our house is now one huge quarry and large limestone carrying vehicles are busy trying to spread beautiful Derbyshire equally amongst every other county in the land. How long will it be before the trend is reversed and the quarries will become natural landfill sites and every other counties waste and rubbish is brought back to fill them? The down side of the hill now has pre-formed metal barriers to protect the houses and these in themselves are an eyesore.

-

Regularly, perhaps twice a year we used to go by train to Normanton to visit both sets of grandparents and Aunts and Uncles, most of whom still lived locally at Normanton. As dad was a railway man we travelled on his allocation of free passes, otherwise I do no think it would have been possible. I for one used to enjoy these trips. I have always liked trains and travel.

-

In the summer of 1933 Walter reached 14, left school and started work at Masson Mill just a few yards from Cromford Market Place on the road to Matlock Bath. Also in 1933, 16 October to be exact we received a new addition to the family, Eileen was born at Wirksworth Cottage Hospital. I was considered too young by the hospital authorities to be allowed to visit. How times have changed.

-

Life changed for us in 1935. Dad had been ill in the early part of the year, went back to work, took ill again and was taken into hospital, the Whitworth Hospital, Darley Dale where in mid May he died.

-

This was disastrous, for mother in particular, she was left with six children, the youngest being only 18 months old.

-

By this time I think, Walter had started work at the LMS at Derby MP depot as an engine cleaner. This meant generally cycling to Ambergate, catching a train to Derby, then back to Ambergate and cycling home. Nellie had started housework at a house near school but I am not sure if she had left school by then. She subsequently moved with the family she worked for to Devonshire, Woodbridge I think. This left four of us as total dependants.

-

Within weeks of dads death Mother was approached by the Secretary of the Railway Servants Orphanage in Derby with a view as to what could be done to alleviate mothers situation. The result was that they would take two children off her hands until they were old enough to leave school. I do not know how much heart searching it cost her but the logical choice was eventually made, Kenneth was nearing thirteen, Colin was just eleven and I was nine in the June of that year and Eileen was still very young at 18 months. Colin and I were selected to go to Derby. I’m sure neither of us wished to go but needs must, and came that fateful day in August 1935 mother took us down to Cromford station and then by train to Derby. A number 22 trolley bus took us through Derby to the Ashbourne Road and stopped outside the orphanage. As we three began to walk up what seemed to me a very long drive I can remember feeling rather overawed, the drive was long and the building at the top was huge and vaguely unfriendly, built of stone which had darkened and with architectural features more imposing than likeable, and we had just ridden right through the centre of Derby! The largest building I had seen so far was Cromford School or the Greyhound Hotel and this building seemed many times bigger than both of them. There was also a very big and imposing building dominating the right hand side of the drive which I don’t think helped. This turned out to be Ashbourne Road school.

-

The drive curved round to the right as we approached it, there was an imposing front entrance but that was not for us, a side door appeared and mother pressed the bell. We were met in a friendly manner, and after a little while for acclimatisation it was suggested that mother leave us. This left Colin and I a little bit dazed and bemused, a little bit unhappy and probably apprehensive.

-

It turned out that the entrance we had used was on the girls side of the orphanage and was the entrance normally used on arrival. We were taken through the building to the boys side and there we met up with some of the staff who would be looking after us from then on. To me the inside of the building justified looking as big as it did from the outside. There were corridors and doors all over the place, the ceilings seemed very high and made the interior seem cavernous. At this time there were about 240 children at the home, 140 boys and of course 100 girls. The girls were supervised by an all female staff headed by a matron, the boys had female supervisors for the younger ones and a Boys Warden for the older ones and he was in overall control of the boys side.

-

Both sides, boys and girls were segregated into age groups, primary, junior and senior. Being only 9, I was placed in the primary section and to my concern Colin was put in the juniors. So basically we were separated. In one short day we had gone from a happy family home in a small village to being on our own amongst total strangers in a strange town which might as well have been many miles away from Cromford. It was no comfort to me to find out later that most of the children came from much further away than we did. We were amongst the closest to Derby. One mile or a hundred, there was no difference.

-

From the outset I did not like being in the orphanage and never did like it although I got used to it. The seven years I spent in their care did not leave me with any memories of that time being part of a happy childhood, that said, we were not ill treated or uncared for, quite the contrary. There was a sanatorium and a trained nurse in charge for any child who was unwell enough to need care and segregation but not needing hospitalisation. Clothes were of serviceable quality but all the same thus constituting a uniform. Food was predictable and unexciting, after a few weeks one could recite the whole weeks menu and this was, in the main rigidly adhered to. It had to be eaten too, one was not allowed to leave anything not liked. It would be served up at the next meal until it was eaten. Polony on a Saturday morning was a horror for one boy and several times he would still be there when the rest of us came to the dining hall for tea! If we could find any takers, unwanted food would be given away to neighbouring boys at risk of being caught and punished. Polony, however was universally disliked and so this boy could never find any takers. The last mouthful could be smuggled out in a handkerchief.

-

This discipline on their part could have had dire consequences, one weekday morning I was attacked by stomach pains which I still remember as being very severe and I was feeling quite unwell and began sweating and becoming paler by the minute, the boys near me began asking questions, I could not eat anything and gave the food away, I did not improve and they called a prefect who called the supervisor and I was helped to the nurses surgery, and there I was questioned and my temperature taken made to lie down on the couch, after some time she asked me if I had eaten my breakfast and I had to say yes or get the other boys into trouble, thinking about the pain I was feeling and in hindsight years later I feel that she believed I had bolted my food and it was my own fault . I found out later that the food had been put back on my plate. Fortunately the pain did subside and there were no ill effects.

-

Girls and boys were strictly segregated and were not allowed to talk to each other, and this included brothers and sisters, they were allowed to meet after the evening meal twice a week, Wednesday and Sunday for half an hour on each day, and this would be the only time they could exchange letters from their families. As we were also in separate sections at school, we orphanage pupils without sisters never met with girls either in conversation or play. After school we had to go straight back to the orphanage in crocodile formation, the same as we came to school, We were not allowed to leave the orphanage so we could not mix with other boys and girls as was normal.

-

I was at Ashbourne Road school for two years and passed the scholarship for a minor secondary school, September 1937 saw me starting at the Central School for Boys in Abbey Street Derby. There were about ten of us who attended there and it was assumed that having passed the scholarship we were capable of being trusted to make our own way there and back, this applied also to those who went to Bemrose School, St James School and Derby School, but we were still not allowed to mix after hours, and there were no girls at any of those secondary schools. Colin meanwhile had attended Kedleston Road School.

-

There was no privacy in the orphanage, common washroom, bathrooms and dormitories. Any homework had to be done above the bustle and noise of perhaps 30 or 40 other boys who did not have homework. Generally speaking the only times we left the confines were for school, church and visits. Visits were allowed once a month on the first Saturday from 2-6pm. Sometime in 1938, mother found a place to live in Derby and it made sense as Walter and Kenneth were at work on the railway and Eileen was just old enough to start school, we two boys were already in Derby. Firstly Mother was in lodgings in Dairyhouse Road and within a few months the local council had accepted her application for the tenancy of a council house. This turned out to be a three bedroomed house, coal fired back boiler, bathroom internally and a toilet, whilst access was from the outside it was built within the confines of the house, and the whole estate was relatively new and up to date for the period. There was also a substantial garden and I think mother must have been quite pleased and satisfied with the improvement in her situation. This was 22 Hawke Street, Derby and was only about a quarter of a mile from the orphanage. This improved her situation, Walter no longer had to cycle 14 miles a day and also saved time. Kenneth started as an apprentice fitter. Eileen started school and Colin and I were much closer to home.

-

At the long summer holidays we were allowed to go home for the six weeks or so and this was the only time we were allowed home, but since the move to Derby we could go home on the monthly visits also. 22 Hawke Street was destined to be mothers home until she passed on in 1984, some 46 years.

-

The long summer holiday of 1939 was nearing its end when the Second World War was declared and I vividly remember that day, The Prime Ministers broadcast announcing the fact that we were at war with Germany and the air raid sirens being sounded only minutes later. Behind the scenes of course many things began to happen, but immediately, as far as I was concerned we were told to stay at home until further notice. Colin had reached the magical age of 15, left the orphange and obtained work. I am not sure of the exact timetable but the orphanage was under notice of requisition by the Armed Forces and the children were to be evacuated to country sites out of Derby. To return to that summer holiday. For me it lasted about three months, and for several weeks mother would pack me up some sandwiches and I would walk down to Ashbourne Road around 8.30am and be picked up by a Mr Curtis who was a friend of the family from Wirksworth and now living in Chaddesden, he drove a lorry for a firm called Mort and Taylor who were contracted to British Celanese and used to run regularly towards the mills of Nelson and Blackburn. Sometimes we went right into Nelson but more often we changed lorries with another driver doing the opposite run. I came to know the route up to Manchester quite well. Ashbourne, Leek, Macclesfield, Hazel Grove, and Stockport. In retrospect I thoroughly enjoyed every mile and it was a sad day when we met the incoming driver and Mr Curtis was given notice of redundancy due to the war situation. But as they say, it’s an ill wind etc., he was 41 at the time and over the age of call up to the forces and thousands of young men were being drafted into war service so he soon found suitable employment. I must have seen many more places and travelled many more miles than I had in my life up to that time.

-

We were recalled to the orphange early October and whilst there, there was a thunderstorm and the lightning brought down quite a number of the barrage balloons in flames.

-

The organising of the evacuation of the children must have been quite complicated. If I remember correctly, the primary boys and all the girls went to Foston Hall. The Derby School boys went with their school to Woolley Moor near Ashover. The senior boys were billeted on the people of Pilsley somewhere east of Clay Cross. The junior boys and the secondary school boys went to occupy Park Lodge at Fritchley, between Ambergate and Crich. This is where I went in October and started to attend Swanwick Hall school. a county grammar of good reputation between Alfreton and Ripley. In due course, and it was only a few weeks the boys at Pilsley joined us at Park Lodge. They then attended Mortimer Wilson school at Alfreton.

-

Park Lodge was, and still is on the east side of the road from Bullbridge to Crich on a very steep hill just by the turn off to the village of Fritchley. It was an interesting house in its size and layout. Its main entrace faced south and was flanked by two bay windows. These extended to the second floor and one was surmounted by a spired turreted room. Externally it appeared mainly as a two storied building but there was space above which was interesting to explore and was used as bedrooms, and the turreted part enclosed a small room which gave extensive views over the Amber valley, particularly towards Ripley.It was stone built, basically square in plan. It was built with accommodation for house staff with a large kithen, storerooms, a servants staircase, large cellars, and to the rear there was a small yard bounded by stables and equipment rooms all surmounted by a loft. There were were substantial plantings of shrubs, a large kitchen garden, an orchard and a field of about two acres fronting the road.

-

Park Lodge, the building itself was a world away from the orphanage building in that it was built as a home and not an institution, the proportions and design were smaller and homelier. We were allowed more freedom than at Derby, there were no girls to be segregated from and we had the run of all the property except of course for the staff quarters, and of course it was in the country which suited me fine. On the roadside over the top boundary wall there was one of those short prism shaped milestones indicating that five miles further on through Crich lay Cromford!

-

School at Swanwick was reached by the Trent 104 service from Belper to Alfreton which we boarded at Bullbridge. We were given individual bus passes each term which helped our ego a little. The bus went via Buckland Hollow and Pentrich which was open country all the way, a vast difference from walking the streets of Derby where no blade of grass was to be seen.

-

The school was also a world away from Central School in Derby and could not have been any more different. At one time it was a large private house to a locally important familly, it had come under the control of the County Education Committee and by this time it had been added to and enlarged with the addition of classrooms, workshops, assembly hall and other facilities, it was obviously a school but it had been done quite sympathetically and the result was a pleasant school set in many acres of mainly sports fields, tennis courts, gardens and ornamental trees. The main building was brick built and these had mellowed to an attractive shade and over the front elevation I remember a pear tree which had spread itself like a giant ivy.

-

Although the numbers varied, we, the orphanage boys numbered around ten and we were still affected by the regime of the orphanage in that we were all dressed alike and had no money of our own to spend and had to catch certain busses or explain delays. We could not arrange to see other boys after school as we were allowed no social life outside our own circle even at weekends.

-

The school was of a much higher standard than the one I had left in Derby and at first the syllabus was completely different and further advanced so that a period of difficulty was experienced until we made some progress towards catching up and adjusting to the altogether new situation. The biggest single change among so many was that Swanwick Hall was co-ed, and for the first time since I was at school in the infants class at Cromford, four years previously, I was meeting girls on a limited basis, it was certainly an improvement but the gap was great and I still feel that the strict segregation we had to endure throughout our orphanage life was a great mistake.

-

I was never a great student, but, within its obvious limitations, I enjoyed my time at Swanwick and still have quite a regard for the school and the pupils I met there. Mostly it was fee paying school which usually meant that the pupils had few, if any, money worries, and had regular amounts of pocket money which we never had, but although there was interest and occasional disbelief in our situation I do not have any real recollection of being shunned or being treated any differently by any of the staff or pupils.

-

To return to Park Lodge, as I have remarked, we certainly had more freedom there than in Derby and on certain occasions, such as school holidays, we were allowed out of the grounds in pairs with no questions asked to roam around the local area. This local area being hill, trees, a river, country pathways and minor roads and a canal, I was in my element. There was also the railway station at Ambergate which was busier than at Cromford. There was also a light railway of George Stephenson origin from Crich Quarries to the lime burners at Ambergate, these were fed by wagons full of limestone being lowered on a cable controlled incline to the lime burners. These were about twelve large furnaces and the stone was loaded in from the top, the noise, flames, smoke and dust was sight to see and remember. As the railway was the result also of George Stephenson’s ability I suppose from the early days it was used to transport the finished product and a sidings was certainly in place. The arrangement of this sidings was unusual to me in that the wagons were individually turned through 90 degrees on a small portion of the line built as a turntable and run of at right angles into the lime burning area. Near Bullbridge there was also a small brickworks and without hindrance we could watch the raw materials from the quarry going down the chute to be ground into powder by the large grinding wheels below, but of the actual process of manufacture I never did see anything.

-

Being wartime of course, many restrictions were imposed countrywide but very few seemed to affect us directly. The blackout was one of course and heavy double curtains were installed everywhere at Park Lodge, we had many air raid warnings but never any hint of danger to this area, Derby sufferred some damage but the numerous warnings we received were probably due to being on the flight paths to centres like Sheffield, Leeds, Manchester and Liverpool, all of which sufferred heavily.

-

Rationing was also in force and in the summer we used to collect pounds of blackberries and wild strawberries and raspberries and the staff made jam which kept us supplied until the next summer. I do believe that an extra sugar ration was available for the purpose. The orchard was still in plentifull production with gooseberries, black, red and white currants, apples, pears, quinces and greengages. The original gardener was kept on and he grew the usual supply of vegetables in plenty, so foodwise I think we must have done quite well, vital rationing apart of course.

-

Having said that we were not affected by the war, we were well aware of its progress as we all listened to the news in the early evening and as it was repeated at dictation speed I adopted the habit of writing it down in excersise books. From Dunkirk. the Battle of Britain to the Desert War and the start of the bomber offensive against our country to the start of the offensive against Germany from the air. The major course of the war became imprinted on my mind. Needless to say I have no idea what happened to those excercise books.

-

Healthwise we were subjected to regular attacks by a visiting dentist and barber and looked after by a Dr McDonald’s practice from Crich. The usual young peoples ailments affected the group, a broken arm, boils, one boy was subject to epilectic fits and the first couple of times were distressing to observe, there was a case of rheumatic fever which I think at the time alarmed us. Myself, I was subject to throat infections and had been in the sanatorium at Derby for a few isolation days on a couple of occasions and had had the then almost mandatory tonsils op at the Derbyshire Royal Infirmary when I was ten. Here at Park Lodge however I developed Quinsy for which the doctor recommended that I be isolated. This meant that all the boys in one bedroom were moved into the remaining rooms which meant a modicum of overcrowding. The infection turned septic. When I finally returned to school, the teacher welcomed me back and as part of the conversation remarked that I had nearly died. This threw me completely and my only reply was a self conscious grin which I don’t think impressed him. I had known nothing of the seriousness of the infection, only the utter discomfort and pain of a very sore throat.

-

Eventually 1942 came round and by then Nellie had been in the ATS for several months and was serving with the Royal Artillery on Anti-aircraft defences around the East Coast. Colin was called up for military service and reported to the army at Horncastle in Lincolnshire. Mother had obtained work at the LMS on the canteen staff at the Carriage and Wagon Dept at Litchurch Lane in Derby. Kenneth and Walter were in reserved occupations and would not be called up. Kenneth was transferred to the Coalville Depot in Leicestershire and was in lodgings there. In July Walter married Joan and they had set up home in Queen Street Derby. I sat the School Certificate exam and reached my sixteenth birthday at the end of June, so when school broke up for the long summer holidays I left Park Lodge and returned home to Hawke Street after having served almost seven years.

-

I started work on the LMS as a messenger in the Night Office and worked regular hours of early, 6am to 2pm and late, 2pm to 10pm. until about a year later I sat and passed the clerical exam and was moved to the parcels office as a parcels booking clerk on the same hours of work. I had become a member of the Air Training Corps and soon after my seventeenth birthday volunteered for aircrew in the Royal Air Force. I went to Hornchurch in Essex for tests, I passed the aptitude and medical but informed that at that stage of the war there were no vacancies for Pilot/Navigator and was offerred Air Gunner. This I refused and decided to wait for call up to the Army. I was transferred to the Enquiry Office in Victoria Street, in the centre of Derby. This was normal day work of 9am to 5pm.

-

One morning in late May as I was preparing for work and the only one in the house I answered the door to a knock and a Post Office Telegram messenger handed me a telegram, I was devastated to read a message from the War Office that Colin had been killed in action at Cassino in Italy. I immediately went to Walter and Joan and from there Walter and I went to the Carriage and Wagon canteen and had to break the news to Mother.

-

In June 1944 I had to register for military service and in the middle of August was required to report to Lincoln Barracks for initial training. So, within two years of leaving the orphanage I was again back into institution type life.

-

The first six weeks at Lincoln were the same that all draftees had to endure at that stage. Basic discipline, kitting out, issued with rifles, care of kit and arms, medical examinations, aptitude and selection tests, basic drill and instruction and range firing.

-

During that six weeks ones future was basically decided on the result of the foregoing tests and personal interviews. I was selected to go for extended training with a view for selection for Officer Training. In October 1944 I and others were posted to the 28th Training Battalion at Palace Barracks, Holywood, County Down, N Ireland, just a few miles outside Belfast. Such was, and no doubt still is, the perversity of the military mind that the 27th Training Battalion, doing exactly the same job was established on Markeaton Park, Derby, just a quarter of mile away from home. On arrival in Ireland training began in earnest and was to last six months instead of the usual 10 weeks if one was destined for an Infantry unit. During that time we were constantly assessed and eventually faced a War Office Selection Board, as the war was then looking towards final victory, the need was not so urgent and selection was that much harder. On average at that stage we understood that only 3% passed selection, on our course it was 1% and that did not include me.

-

Sometime just before Christmas we were suddenly issued with live ammunition and put on standby to move. We were not told why but it later turned out that coincidental with the massive German offensive in the Ardennes and the ensuing Battle of the Bulge, it was feared that a possible landing may be made by German forces into neutral Southern Ireland, we and the others training in N Ireland were the nearest troops and there were no reserve Infantry divisions left in the UK.

-

Earlier in the November we were spoken to en masse by a Sgt and Captain from the Parachute Regiment who were looking for volunteers. four of us put our names forward and we heard no more until February 1945 when we completed our training and were posted to our new units.I was initially down for the West Yorkshire Regiment, as I was born there that was my initial choice, but I was to report to the Airborne Forces Depot in the grounds of Hardwick Hall, 8 miles from Chesterfield in Derbyshire. Training began immediately and was deliberately hard. All trainees had to double everywhere whilst within the camp bounds, assault courses, forced marches and physical training were the everyday routine for two weeks, whatever the weather was doing. No drill, no weapon training, no lectures, nothing but hard physical effort. All that fortnight we were being observed and assessed by the Instructors, Doctors and a resident psychiatrist. Physical and mental fitness was required plus the mental determination to keep going as long as possible when the going became difficult. Passing out from there we were marched with full kit into Chesterfield railway station and entrained for Manchester airport, then known as Ringway, for our parachute training, by then to all intents and purposes we had been accepted by the Regiment and only had to pass our jumping course satisfactorily. Contrary to Hardwick Hall, here (at Ringway) it was very possible that the weather could delay proceedings and being February and March borders it certainly did, our scheduled two weeks stretched to three, and three jumps had to be done in one day for us to complete our eight in total, this had to be done as other courses were coming up behind us and too much delay would cause havoc to the overall training programme. It was a course completely under the control of the Royal Air Force and we were treated, by military standards, like visiting royalty, the food was plentiful and very good, the relationship between the Army and the RAF personnel was very easy going and friendly. Parachuting in that era was a relatively new concept and considered a foolhardy and dangerous occupation so perhaps they thought we were a little bit mad to be doing it. The course itself was stimulating and of course had its moments but it was completed successfully apart from one fatality. We were presented with our wings and red beret and from that moment we were members of the regiment. It was a proud feeling.

-

I was entitled to two weeks leave and was slightly apprehensive of meeting my mother. I had written to Nellie and told her that I had joined the Parachute Regiment, but I had not told mother. I thought it better to present her with a fait accompli rather than let her worry too soon, as she undoubtedly would have done, having lost Colin less than a year previously. Had I told her as soon as I had volunteered in the previous October, Colin had only been killed 4 months previously and it was nearly another six months before I joined the regiment. She did berate me a little but there was nothing to be done.

-

After my leave was over I reported back to Hardwick and the following Monday I was posted to Bulford in Wiltshire to join the 7th (Light Infantry) Battalion of the regiment, only to find that the 6th Airborne Division had just that weekend dropped over the Rhine. Only holding staff and reserves were at Bulford. Having been a railway clerk I was co-opted into the Orderly Room to help out and for the next two months it constituted an easy work load, little pressure and generous 36 and 48 hr passes most weekends unless one was scheduled for guard duties. Whatever we might have been scheduled for, came VE Day, and we newer members of the Battalion were on all duties around the camp to allow all members who had seen action to go to the nearest towns to celebrate the victory they had helped to win. I was put on guard at the main gate and it was quite enjoyable greeting back to camp those who had been celebrating. After a few days we new ones were given two weeks embarkation leave and the rest of the division who had just returned from Germany were given 2 weeks disembarkation and 2 weeks embarkation leave, under orders for the Far East, as the war with Japan was far from over and still very much alive. Still being in the orderly room at the time I was one of those detailed for the Advance Party which was to fly out in advance of the remainder who would follow by sea. Things moved fairly quickly and by the middle of July we were in India, at Kalyan a few miles inland from Bombay. The advance party was for a Brigade only and that brigade was made up to strength and was immediately sent out by sea. Within a fortnight of our landing in India, the remainder of the brigade had joined us. The two other brigades making up the remainder of the division were at sea when the atomic bombs were dropped and Japan surrendered. They were diverted to Palestine as part of the Middle East Strategic Force. Almost immediately with the end of the war, the Jews began agitating for Palestine to be earmarked as their homeland. and subsequently all British Forces in Palestine were engaged in keeping the peace. Sometimes at great cost to life and property.

-

As I see it now, our role in the Far East was to release all allied prisoners of war, military and civilian and stabilise the area by control and organisation of civil government. We sailed from Bombay and eventually (after an abortive beach landing) landed in Singapore, where dock duties were our main concern. The Japanese had encouraged the rise of nationalism in those territories which were colonial and trouble brewed in many areas. For my story, trouble brewed in the East Indies and as the Dutch who were the colonial power had not recovered fully since liberation, could not send troops and asked the British Government to regain control of the Dutch East Indies and restore and maintain civil order and peace. We were first in Batavia and after about a month our Brigadier asked for a town in which we could be the sole troops and were flown to Semarang. This was pleasant town and was ringed in horseshoe fashion by hills. the 7th Bn was fortunate in being given the duty of protecting this perimeter. It was cooler and we were billeted in Dutch colonial houses. All the three battalions sufferred casualties but by the time Dutch troops arrived we were firmly in control, and had the co-operation of the main civilian population, so much so that, when we left the town by sea in April 1946 it seemed the whole population was there to see us off and to wish us well.

-

Back in Singapore we moved up country by stages, two weeks at Kluang, a month at Grik in Perak,and then by rail again we crossed the border into Siam and circled back on the East coast to settle in a small village on the Siamese side of the River Golok. Ostensibly we were there to prevent smuggling across the border with Malaya, but really I feel it was the early stages of the Malayan Emergency which was to claim quite a number of lives on both sides and last for several years.

-

We came back down to Port Dickson on the Malacca Straits coast for a few weeks and within a year of landing in India we had rejoined the remainder of the division in Palestine. We called at Madras and Colombo on our way back to Port Said. A 24 hour rail journey with accompanying sandstorm greeted us into Palestine. Our first posting was the very airfield we had touched down at on our way out to India a year previously.

-

There were two main areas of Command in Palestine, logically North and South, and every so often the troops were changed over. We had not been back many weeks when the changeover was due and we went North, we had been in three camps in the Southern area, Nathanya, Kfar Vitken, and Petah Tikva. In the North, our Battalion was given the north of the north and were split into four camps. (A company to each) centered around Rosh Pinna and Safad. The other two battalions were based in Haifa.

-

After around 18 months overseas service one became due for a months leave in England and I came home in time for Christmas 1946, rejoining the Battalion in Palestine in early February.

-

We did three refresher parachute jumps in the south of the country, and in late summer of 1946 we were moved into the city of Haifa, patrols, roadblock checkpoints and general security duties became the order of the day.

-

Whilst in Haifa, my demob number came round and I said my goodbyes and returned to England and on to York for demobilisation and I was home in Derby on Christmas Eve 1947.

-

I was aged 21yrs and 6 months and I had been away from home for a total of 10 years and 5 months.

|

|

Hello John,

We first had contact in October last year, about a house at

54 The Hill Cromford, and you kindly tried to help, one result was

that you entered my part biography on your Wirksworth site, our

last exchange expressed my intention to keep in touch.

The part biography you entered on your site bore fruit a little

while after. An O'Shaughnessy read it and started to enquire via the

phone books for this area and eventually contacted a nephew of mine,

who contacted me without revealing any info and I called him. He

turned out to be a first cousin, the branch we had lost touch with

due to his father Peter, (My Dad's brother) leaving the area the family

lived in. All I was ever able to find out was that he had moved to

Morecambe for work on the Heysham Docks and that he had married a

Mary Jelley. This line of the family has now been filled and extended.

Peter, the 'new cousin' was overjoyed for one or two reasons, firstly

his father was killed in a road accident and was buried on the same

day as he (Peter) was being born, so he never knew his father.

Secondly, because they had moved away, much the same way as we did,

intimate contact with the family was virtually lost and with the

passing of the years much information was also not assimilated. I

was able and pleased to be able to help him fill in the gaps with

about 500 associated names for him to digest.

So, thanks to you and the enormous amount of work you have done

with your site, part of a muddy path has now been tarmaced, and is in

process of being concreted.

Thanks once again John

Yours, George O'Shaughnessy

Hello John,

We first had contact in October last year, about a house at

54 The Hill Cromford, and you kindly tried to help, one result was

that you entered my part biography on your Wirksworth site, our

last exchange expressed my intention to keep in touch.

The part biography you entered on your site bore fruit a little

while after. An O'Shaughnessy read it and started to enquire via the

phone books for this area and eventually contacted a nephew of mine,

who contacted me without revealing any info and I called him. He

turned out to be a first cousin, the branch we had lost touch with

due to his father Peter, (My Dad's brother) leaving the area the family

lived in. All I was ever able to find out was that he had moved to

Morecambe for work on the Heysham Docks and that he had married a

Mary Jelley. This line of the family has now been filled and extended.

Peter, the 'new cousin' was overjoyed for one or two reasons, firstly

his father was killed in a road accident and was buried on the same

day as he (Peter) was being born, so he never knew his father.

Secondly, because they had moved away, much the same way as we did,

intimate contact with the family was virtually lost and with the

passing of the years much information was also not assimilated. I

was able and pleased to be able to help him fill in the gaps with

about 500 associated names for him to digest.

So, thanks to you and the enormous amount of work you have done

with your site, part of a muddy path has now been tarmaced, and is in

process of being concreted.

Thanks once again John

Yours, George O'Shaughnessy