Brassington

a summary history based on Lands and lead miners (1991), by Ron Slack.

Prehistory

Brassington lies in a steep north-south valley running down from the edge of the White Peak. To the north is the plateau of Brassington Moor, to the east the high rough ground of Carsington Pasture and to the south the South Derbyshire Plain. The name is Anglo-Saxon - Brand's people's place - and the Saxon settlement was probably founded in the 5th or 6th century, after the departure of the Romans.

Archeological finds have established human habitation of the surrounding high ground from paleolithic times, and there were British settlements at Harbough, Roystone Grange and Rainster Rocks during the Roman occupation. A substantial Roman settlement has been found near the Scow Brook at Carsington on ground now covered by the water of Carsington Reservoir, and the Roman road from Derby to Buxton, the Street, passed over Carsington Pasture. The Scow Brook settlement has evidence of lead working, and Roman lead ingots - "pigs of lead" - have been found on Carsington Pasture. The inscription "Lutudarum" on Roman pigs of lead probably refers to a place or a company in the Carsington area.

The Saxons cleared the ground to the south and farmed it communally, in strips, or "lands", which can still be seen in the form of ridges. To the north, east and west the land was uncultivated "waste", held in common for grazing and collection of turf, timber and stone. Their route to neighbouring Carsington skirted the high ground and the Roman Street eventually lapsed and disappeared. By the time of the Norman Conquest the Brassington settlement had become an estate, or "manor", owned by a nobleman called Siward. The manor was one of many granted by William I to Henry de Ferrers and was run on feudal lines - the villagers held their lands in return for working on the lord's home farm and paying him many onerous dues. The lord's manor court met regularly, setting and enforcing farming rules, granting title to property and punishing minor offences.

Mediaeval Brassington

For 250 years after the conquest the population grew and the villagers expanded the cultivated area westward beyond Rainster Rocks and eastward up the slopes below Carsington Pasture. It was during this period of prosperity and expansion that the village church was built, in the late 12th century. Until the 19th century Brassington was a part of Bradbourne parish and the church, dedicated to St James, was a chapelry of the mother church at Bradbourne, serviced by the Bradbourne vicar's curate.

In the 12th century half of the manor was granted to a De Ferrers heiress and this half, whose ground was scattered among the lands held by the old manor, was run as a freehold estate. The remaining feudal manor was taken from the De Ferrers family in the 13th century and given to a son of the king, the earl of Lancaster. His successor in the following century, by then Duke of Lancaster, became king as Henry IV in 1399 and the manor remained in royal hands until it was sold by Charles I in 1632. The records of the Duchy manor court from 1300 until 1632 are preserved in the Public Record Office. From the date of the sale in 1632 until the formal abolition in 1925 of the feudal system of land tenure known as copyhold, the manor was held by Derbyshire gentlemen and its records are now in the Derbyshire Record Office.

During the 14th century a succession of calamities reversed the progress made since the Conquest. There was a major climate change to wetter and colder weather, a ruinous cattle disease and finally, in 1358, the Black Death. The effect of this on the village can be seen in the manor court records, which ceased altogether for several years, and which resumed with most of the family names of the years before the plague gone. The cultivated fields on the west reverted to wasteland and the shortage of labour to cultivate the land caused the Duchy of Lancaster to abandon the rigours of the feudal system. The manor court still ran things but the villagers now held their land by money payment and owed no other dues to the lord. When, under James I, the Duchy tried to reassert its ancient rights, the villagers established that they owed "ne works nor boones nor other duties" to the lord.

Out of the Middle Ages

The old farming methods began to change in the 16th century, when adjacent strips were progressively grouped into the fields, bounded by hedges, which still exist to the south of the village. These "enclosures" were usually by agreement between the owner of the freehold estate, by then the earl of Shrewsbury, and his tenants, and between the Duchy and its tenants. However, the creation of privately-owned fields meant that less and less land was available for communal grazing during winter or during the year when a third of the lands were left fallow, and the enclosures were often opposed by the villagers who relied on the old system. These struggles were sometimes forcible, sometimes legal. By the middle of the 17th century the present field pattern in the south was established. Arable farming was largely abandoned and the new fields used for stock raising, which is why the former strip ploughing patterns survive. The waste continued in common ownership until the beginning of the 19th century, with most of the grazing rights owned by the large land owners, who rented them to the villagers.

The 16th century, especially the reign of Elizabeth I, saw a rise in prosperity among the wealthier families in the village, based on the wool trade and lead mining. Some families, notably the Buxtons, Westernes, Trevises and Blackwells, became gentlemen, and their houses became larger and more comfortable with each generation. In 1615 William Westerne, whose description changed from yeoman to gentleman during his lifetime, built the house on Town Street now known, erroneously, as the Tudor House. This was one of the first stone-built houses in the village and still used wattle-and-daub for its internal walls. It was an inn, known as the New Hall, on what was by then the main road between Derby and Manchester. It remained an inn until 1820, changing its name to the Red Lion. Another sign of prosperity was the presence in the village of at least one very well stocked shop, selling all kinds of cloth, from expensive lace and silk to mundane linen. This shop also sold spices and herbs, soap, starch, candy, sugar, garters, caps, tobacco and gunpowder, and much else - over four hundred separate items. There were four alehouses to serve the miners and farmers. They also served the carriers, leading their pack-horse trains between Manchester and Derby - the roads were impassible to wheeled vehicles.

The "poorer sort", to quote a contemporary document, free of the old feudal ties, generally preferred lead mining to farm labouring, which was one reason for the change from labour-intensive arable farming to stock rearing. Mining was at the height of its prosperity in the 17th century, and many villagers became prosperous enough to buy or rent pasture fields in the village to keep a few cattle or sheep. It was during this century that miners began to leave wills, a sure sign of increasing prosperity. There had "always" been lead mining ... the natives whom the Romans set to work mining the veins on Carsington Pasture and Brassington Moor were likely already to have been expert at it. There is evidence of lead mining during Saxon times, and in 1289 Edward I, as part of a survey of the crown possessions known as the "Quo Warranto", ratified a set of rules and customs for the industry which were already ancient. To the men, and women, of Brassington, lead mining was a natural activity and always had been ... Every day, for centuries, there had been men, women and children getting lead from the limestone under the thin soil of Carsington Pasture ... The mines were always there and men in every generation learned the skills to enable them to take advantage of the trade's unique laws and customs. Mining was an adventure, and while prospecting was always a gamble, it had overwhelming attraction to men who would otherwise have been wholly dependent on farm work. Compared with the life-long drudgery of labouring in the fields in the certain knowledge that the master would never pay them more than the minimum needed to survive, that they could be laid off in bad times, that they would be unlikely to save anything for their old age, and that their life's work would leave them bent and exhausted, mining offered independence and hope. The "poorer sorte" preferred to "labour in the lead groundes" because there they were their own masters and because from the middle of the seventeenth century, for about a hundred and fifty years, mining was profitable enough to pay the rent of the few acres which would feed a few sheep, cattle or pigs. Edward I's Quo Warranto confirmed the peculiar rules of lead prospecting ... [which] allowed miners to prospect anywhere except under highways, churchyards or orchards, to make roads to carry their ore away, and to use water, including streams where there were any, to wash [dress] it".

The great changes in land holding, agriculture, village government, religion and in the social pattern among the villagers, which together transformed the mediaeval village, were largely complete in Brassington by 1700. The villagers had long been free men, able to sell their labour where they could, but they could no longer graze their cattle and sheep in winter on the open fields, after the crops had been brought in. For grazing they paid those few of their neighbours whose tenure of most of the land was now exclusive. There was still the open moorland -"the moors and wastes of Brassington" - but here too the grazing had become concentrated in a few hands and most of the villagers had to pay rent for the privilege of grazing their cattle and sheep there. It was still a vital part of the villagers' lives, however, this immemorial wasteland, still unfenced and criss-crossed with the paths to Elton, Ible, Winster, Wirksworth, Hopton. It must have seemed impossible to the villagers that they would ever be fenced out of this part of their territory and yet the landowners with grazing rights there were intent on enclosure and would eventually accomplish it. The crops of oats, wheat, barley, rye, beans and peas were much diminished, replaced by larger numbers of cattle and sheep, while food crops were brought in from places with richer soil than Brassington's thin covering. The manor court still met regularly to carry out transfers of the copyhold fields in the former Duchy manor, but it had finally given up its role in village government by the 18th century. This role was played by the officers of the parish and by the Quarter Sessions of the magistrates' court in Derby, and one of their chief preoccupations was the relief of the poverty which the modern system had created. Modifying the new system were the ancient rules of mining, very important in Brassington during the industry's heyday in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when it was worthwhile for the men of the village to take advantage of them and go prospecting. After the religious upheavals of the preceding two centuries, the eighteenth century curates could attend to their small congregations, teach a few of the village boys their catechism and perhaps more, and baptise, marry and bury their parishioners. They had no competition until the arrival of Methodism in the 19th century, when there was surge of enthusiasm for new faiths, enthusiasm which the parson would no doubt have found embarrassing if he had found it among the pews of the old church.

A workaday village

Brassington became poorer during the 18th century, due to decline in both its main sources of income, wool and, by mid-century, lead. "It was a workaday village, without squire or gentlefolk". The gentry families all left the village and Brassington "changed from a poor community with a few rich farmers and land owners to one which, while still poor, and having no wealthy families at all, had considerably more families who were enjoying a limited and modest prosperity", from the lead trade. However, success in mining could be elusive and this prosperity was fragile - "during a three year period between 1741 and 1744 there were nineteen paupers in a total of thirty-eight burials" recorded in the parish register. Poor families who attempted to move to other villages were soon sent back. Most couples saw half their children die young and every pregnancy was hazardous. Hard conditions bred a tough and philosophical attitude to life and death, often expressed on 18th century gravestones - Short was my time/ Longer is my rest/ God called me hence/ He thought it best.

There was little schooling in the village for the boys and none for the girls. Thurstan Dale, one of Brassington's absentee landlords, left £10 in his will in 1742 to pay the salary of a schoolmaster and one of the earliest, John Johnson, earned a gravestone set up in the village churchyard by his former pupils - "A few of his pupils in grateful acknowledgment have erected this stone". In spite of Johnson's efforts half of the villagers who made wills during his time could not sign their names.

For the first half of the 18th century the village's farmers, miners and publicans kept the advantages arising from its position on the Derby-Manchester road. They were increased in 1720 by a Turnpike Act which improved the road from Derby. Turnpiking was the 18th century attempt to solve the the ancient problem of maintaining a decent road network. Local trustees undertook to raise money by tolls and to use it to pay for regular maintenance. The 1720 Act provided for improvement to the "dangerous, narrow and at times impassable road" between Shardlow, where the London to Manchester road crossed the Trent, and Brassington, where it stopped. The reason for the turnpike ending there was that the route over the upland to the north of the village, the limestone plateau, was dry enough not to need maintenance. Turnpiking was clearly not going to achieve Roman standards, and the road had not advanced beyond Brassington when Burdett published his map of Derbyshire in 1789. An alternative route to the north through Ashbourne was turnpiked by an Act of 1738, cutting Brassington's advantage. A further turnpike in 1758, linking Oakerthorpe and Ashbourne, crossing the old road at Turnditch, must have redirected much northbound traffic westward to join the Manchester road at Ashbourne. By 1777 the trustees, while advertising in the Derby Mercury for December 5th that the annual incomes of the Osmaston and Markeaton gates were £279 and £115 respectively, were proposing to remove the Knockerdown gate. Clearly there was no longer enough traffic through Brassington to pay for the cost of the gate and its keeper. The role which the village had played since its founders had built their huts near the Roman Street was over. Travellers had a choice of inns and alehouses, as in earlier centuries. Newspapers had stories mentioning the Wheatsheaf in 1757, the Red Lion, kept by John Prestwidge, in 1761, and the George in 1768. In 1759 the barmaster, Edward Ashton, advertised his inn in the Derby Mercury for letting. This was the New Inn, bought in 1754 from Job Marple. By 1777 the JPs of the Wirksworth wapentake were granting licenses to three Brassington innkeepers, a number which had risen to five by the turn of the century. The reference to the Wheatsheaf in the Derby Mercury in 1757 was an advertisement by a new landlord which, in addition to offering "good Accommodations, civil Usage, and the most grateful acknowledgements", reminds us that the eighteenth century English knew their place. The inn's services were offered to "Gentlemen, Ladyes, and others". The "good accommodations" at Job Marple's Red Lion, the former "new Hall" built by Thomas Westerne, are amply set out in Marple's inventory of 1755. There was good oak furniture in the "great parlour or dining room" and in the eighteenth century equivalent of the tap room. The dining room had decent crockery, including flowered china coffee cups, and was decorated with pictures and maps. There were six bedrooms, with ash feather beds, and the kitchens and cellars were well stocked with food and drink.

The building of today's limestone village, started in the 17th century, continued through the 18th. By the time Brassington was surveyed and mapped in connection with the enclosure of the moors at the end of the century the village looked much as it did throughout the 1800s, before the building of the new school on Town Street in 1872 and the council houses near it in the 20th century. On the east side of Town Street Rakehouse Farm was built. A group of barns was added to Sycamore Farm, which itself dates from the previous century. The miner's cottage behind Wash Hills Farm was built during the 18th century, as was the house on the east side of Town Street called The Green and the one on the west next to Green Cottage. Brassington Hall, on the north side of Well Street, was built during the 17th century. Two more manor houses were added in the 18th, one on the south side of Church Street, opposite Ivybank, in 1774, and the other on the north side of West End, in 1793. Another farmhouse built in this century was Bucksleather House, whose ancient name was changed to Brookfield in the 20th century. One of the village's two remaining pubs, the Miners Arms, was built in the 1700s. A full description of it was given in the manor court book when it was sold in 1771- "all that messuage house cottage or tenement in Brasson aforesaid with a barn and a stable thereto belonging. And also so much of a garden (adjoining the said house) as extends to the middle part of the middle window in the said house... and also all that messuage house cottage or tenement adjoining to the northwest end of the aforesaid house commonly called Palmer's House". The Miners Arms, like other buildings mentioned here, is a listed building and although the list gives its date as late-18th century, Robert Wayne, who sold it in 1771, had bought Thomas Palmer's house in 1725. The pub is an amalgamation of a number of formerly separate buildings and at least one of its parts was clearly built early in the century. Other 18th century additions to the village were Pleasant House, opposite the Miners Arms, and Church Gate Cottage, on the north side of Church Street. This house, like many more in the village, used to be two cottages. With the turnpike road came toll houses. There was one at Hipley which was demolished in the 20th century and one on the Aldwark Road which was for part of its life a cow shed.

In spite of poverty and hardship the villagers knew how to enjoy themselves. The Derby Mercury had a column of local news which over the years included the occasional item about Brassington. Three of these pieces describe the village celebrating big events. For the coronation of George III on October 22nd 1761 "a large Subscription was raised by the Gentlemen, Farmers, Tradesmen and Miners of the said Town, who bought a fat Cow, which was roasted for the Publick ... a Band of Music, consisting of two Hautboys, and Bassoons, with First and Second Fiddles, by very good Hands, play'd before the People round the Town ... the Evening concluded with the loudest Acclamations of Joy and Loyalty". The village celebrated the centenary of the Glorious Revolution of 1688 with a similar feast - "few places surpassed the Village of Brassington". The fat cow for this day was given by the "principal Gentleman", along with "many Hogsheads of Ale". In March of the following year, 1789, the village took the king's recovery from one of his periods of insanity for another feast day, There were bells ringing, a parade by the band and the church choir, who sang a new song specially composed for the occasion, a bonfire "which contained about five Tons of coals", and two hundred gallons of free beer. Not surprisingly "The evening concluded with the greatest harmony". The villagers also amused themselves with the savage old sports of cock fighting and bull baiting, as well as such gentler past-times as bowling - they levelled a patch of ground on the western slopes to make a bowling green.

Life became harder for the villagers when the common wasteland of Brassington Moor was enclosed in 1808. There had been an earlier attempt which failed because of opposition from landowners in Elton, who had rights on Brassington's common. However, in 1803 the landowners agreed on the terms of an Enclosure Act, passed by Parliament, and over the next five years the 2,479 acres of common land was parcelled out, largely in conformity with existing land holding. Many of the villagers were given small allotments, usually of less than an acre, but outside landowners, "three and a half percent of the total allotment holders, were granted 1,464 acres, or fifty-nine percent of the whole". Enclosure transformed the villagers' landscape. The open moorland vanished, replaced by fields and barns. These new fields, unlike the hedged fields to the south, were bounded by limestone walls, creating what became the typical landscape of the White Peak. The Enclosure Act also provided for "public carriage roads", 30 feet wide, and "private carriage and drift roads", 20 feet wide. The former remain the main roads into the village while most of the private roads were never built. Two which were are Lots Lane, then called Mere Road, and Wester Lane, called Sydes Pasture Road in the Enclosure award.

Chapels, schools and House of Industry

The villagers' traditional jobs in mining and farming declined rapidly during the 19th century. The decline in mining was especially steep - there were still forty-three miners in 1851 but only sixteen in 1881, and the industry had effectively disappeared by the end of the century. In farming the figures tell a similar, though less drastic story. In 1851 there were seventy-six farm labourers and in 1881 only thirty-six, reflecting the end of arable farming. Many families left the village and many of those who remained found new work in quarries, kept busy by the demands of an expanding road programme, and on the Cromford and High Peak Railway, maintaining the embankments, viaducts, track and bridges, as well as on the trains and at Longcliffe "wharf", as the railway's stations were called. The decline was slow, however, and for the whole of the 19th and for much of the 20th century, there remained the shops, shoemakers, blacksmiths, joiners, butchers, tailors, stone masons, dressmakers, cattle dealers, carriers, preachers, teachers which made it a lively and to a large extent self-sufficient community. The villagers had five resident coal merchants, a maltster, a straw bonnet maker and two policemen.

In addition to half a dozen pubs and a thriving friendly society, the Oddfellows, 19 century Brassington acquired three chapels, a much repaired and enlarged church, and a new school, built in 1872. The school, providing elementary education to every child in the village, was founded after the Education Act of 1870, and replaced an earlier one which had been built by public subscription in 1832. The early days of the new school were difficult ones for the Headmasters. The villagers seem not to have taken kindly to full-time education, especially not at harvest time. The first entry in the school log records the headmaster's verdict - "The children are in a very backward state". This remained the situation for more than twenty years, with poor attendance and indiscipline hampering the efforts of a succession of headmasters. They were also hampered by the fact the village had opted not to be financed and managed by a School Board but by village trustees. It depended partly on charity and partly on parents' contributions - "school pence". The situation changed in 1894, when the committee, unable to raise money for repairs to the building, handed over control to the Board of Education. A new and enterprising Headmaster was appointed, and this new man proved to be popular and effective. The school prospered.

The Primitive Methodist chapel was built in 1834 by the church's own members, with the help of a loan of £3 from the Winster Circuit. Twelve years later, in 1846, the Congregational or Independent Church members built themselves a much more ecclesiastical chapel than the Primitive Methodists' very plain building. A chapel for another methodist church, the Original Methodists, was built in 1852 with the help of finance from John Smedley who, in addition to building hydros and Riber Castle, was a fervent revivalist preacher. This third chapel in the village was taken over by another methodist church, the Wesleyans, in 1867, after the dissolution of the Original Methodists. All three chapels flourished, holding joint outdoor meetings and collaborating in evening classes before the 1872 school was opened. The congregation of the old church of St James was also vigorous during this century. A new vicarage was built in 1857, party by subscription, and in 1866 the parish was made independent of Bradbourne. In 1879 the church was renovated and extended. A 19th century photograph of the old church, by then about seven hundred years old, shows cracks in the south wall, and the villagers raised £2000 to repair it. This financed a new south wall, a north aisle and an extended chancel.

For twenty-eight years Brassington had its own workhouse - the House of Industry. A Brassington Poor Law Incorporation, or Union, was formed in 1820 and the village bought the old Red Lion pub from James Swindell for £195 to house the paupers of the villages covered by this new organisation. The 19th century workhouses were grim places, appropriately nicknamed Bastiles. Their unfortunate inmates were at the mercy of the "governor" and in 1830 a song attacking the corruption and immorality of the Brassington governor, Robert Walton, and his wife, found its way into print.

Come all you beggars far and near give ear unto my song/ I've something to relate to you, which shall not keep you long/ It's concerning Mr Sheeplouse, that man of mighty fame/ Has pinch'd the poor at the Bastile and thought it no great shame.

There are six verses and a chorus, singable to the tune of the Linconshire Poacher. Mrs Walton becomes Mrs Clambeggar and she and her husband are accused of starving the paupers and stealing the money for their food, while Mr Sheeplouse is accused of fathering a baby on one of the inmates.

The Brassington Union was wound up in 1844, and its responsibilities transferred to a new Ashbourne Incorporation. While a new workhouse was being built in Ashbourne, the old one at Brassington was too small for a greatly increased population, and the Board of Guardians coped by using the George and Dragon pub as well as the former Red Lion. While there were fifteen inmates listed in the 1841 census, there were seventy-seven men, women and children in the old workhouse in 1845, and another sixty-three in the George and Dragon. "For three years the two old pubs were home to a small army of grey people - men and boys in grey suits and grey shirts, women and girls in grey gowns, grey petticoats and grey shifts. The men and boys were given black woollen hats and the women and girls coarse straw bonnets". Their clothes were fastened by "union" buttons, and these temporary villagers breakfasted on eight ounces of bread and two pints of milk porridge, repeated for supper on every evening but Monday. Their mid-day dinner was nine ounces of meat, a pound and a half of potatoes, a pint of meat soup and eight ounces of bread on Sunday and Wednesday. These were red letter days. On Monday and Tuesday there were no meat and potatoes, on Tuesday and Friday dinner consisted of one pound of dumplings, and on Saturday the paupers had either Monday's soup and bread or Tuesday's dumplings. During the Irish potato famine of 1846, peas and more bread took the place of the scarce potatoes. In 1848 the Brassington workhouses were closed, the inmates marched off to Ashbourne, and the old Red Lion was sold as a private house.

Transformation

Photographs from the turn of the [19th] century show a village which looks remarkably like the Brassington of 1990 [and today 2002]. Most of the houses shown in the old photographs are still here. There are some missing from Hillside and some from the south side of Church Street, near the Gate, but the main difference in the village is that the space between Town Street and Church Street, where the meadows used to be, has been filled by houses. Ashbourne Rural District Council built six between the two world wars and thirty-four after the second, but Town Street, Miners' Hill, Church Street, Maddock Lake, Kingshill would seem totally familiar to a nineteenth century lead miner. He would be disappointed, though, if he called at the Red Lion, Thorn Tree or George and Dragon for a drink after work - only the Miners Arms and the Gate are still pubs. The miner would find the paved streets a great improvement on the wet or dusty streets he knew, and he would be profoundly grateful for two other twentieth century improvements - electricity and tap water. The electric mains came to the village in 1930, street lamps a year later, and mains water in 1939 (1). In that year the villagers ended their centuries-old routine of taking their buckets to the well. These innovations, followed in 1951 by the installation of a sewage scheme, were revolutions in the villagers' lives, making their everyday existences quite different from their ancestors'. The village looked the same, but there had been a bigger change in the experience of living there during a few years of this century than during the whole of the previous three or four.

Some changes were delayed. There was still work underground for a few until the 1950s. The mineral extracted from the old lead mines in the twentieth century was barytes, ignored until then but in demand as a source of barium in the modern chemical industry. It was taken from Great Rake and Nickalum until 1919, from Conway Knowl until the 1940s, and from Golconda .. until 1953. The compressed-air drills used in these latter days are still lying at the sides of the mine roads, over four hundred feet underground, at Golconda. Some of the men who used them are the last miners still living in Brassington.

Until the 1950s there was little change in the economics or method of Brassington's beef and dairy farming and there are still sheep grazing the hilltop pastures of the former wastes of Carsington Pastures and Brassington Moor. There were still farms in the village itself. Kelly's Directory of 1936 lists twelve farmers and four "cowkeepers" living in the village and cattle continued to be driven through the streets to and from their milking sheds. Haymaking was partly mechanised. The grass was cut by horse- or tractor-drawn mowing machines and drawn into rows by horse-drawn rakes. There were machines which turned over the rows of mown grass -"swathe turners"- and threw it about to air it -"tedders". The hay was still, however, picked into carts, either drays or muck carts improved by "gormers" to raise the sides, and led to stacks or barns. Even more ancient methods were still used. At least one of the "cowkeepers", with a smallholding on the steep slopes of Yearnstone, cut the sparse grass with a scythe, turned it with a pitchfork, and then loaded the hay on to a tarpaulin and dragged it down to the stack. On all the farms the hay, by then compacted, was cut in winter with a broad-bladed knife, and fed to stalled milk cattle or to stirks wintering in the fields.

In 1936 there were thirty-one farmers in the whole parish, six of whom farmed over one hundred and fifty acres. This was a drop of twenty-three from the 1881 census figure, and very many fewer men were needed to work their mowers, tedders, turners and horse-rakes than when lines of scythe-men cut the grass and the rows were turned and tended by men and women with pitch forks. That there were still haybarns in the village and still cows driven along its streets and milked in sheds at West End, on Town Street and Nether Lane, meant that the sights, sounds and smells of farming still filled the village, but the farms employed only a minority of the people by the middle of the century. There has been fundamental change in the last forty years.

Haymaking has become a task for one man, his tractor and a bailer, or has been superseded altogether by silage making. Machine milking has replaced the man or woman on the milking stool and dairy farming has moved out of the village to the larger farms in the parish. The only farming operated from the village itself is cattle- and sheep-grazing on the moors.

As farming followed mining into history, as far as being a large-scale employer is concerned, the decline in the village's population continued, to five hundred and thirty-two in 1961. This was a fall of ninety-one from the 1951 figure and was the steepest drop in any decade for which there are records. It has been stable since then, falling slightly to five hundred and twenty-seven in 1971 and rising again to five hundred and fifty-eight in 1981.

For the first half of the century Brassington, while declining as a working village, kept its old character. In 1936, in addition to the farms, there were still a butcher and eleven other shops. Three of them sold clothes, including Brindley's, on Church Street, in the building which had been the George Inn in the eighteenth century. In 1936 Thomas Brindley was described in Kelly's as "grocer, draper, clothier and patent medicine vendor". Even more like a great universal store was Ernest Taylor's shop. He was a "grocer, confectioner, tobacconist, ironmonger, wireless apparatus, cycle agent and battery charging". In the village Ernest Taylor's wirelesses would be plugged into the mains by 1936, but most of the outlying farmers would still need to bring their batteries in for charging. Another draper, Joseph Brown, sold and repaired shoes, and there were still two shoe makers - John Melior on Kingshill and George Walker, carrying on his grandfather's old business. Stanley Allsop sold sweets, Frank Stevenson vegetables and fruit and Mrs Hall carried on a small trade in drapery from her home at Stile House. There were a newsagent, Mrs Yates, and a branch of the Wirksworth and District Coop. At Maddock Lake, in the middle of the village, Oulsnam and Fearn's "steam saw mill and timber yard" added the sounds and smells of sawing wood to the village's working atmosphere.

In 1936 the men of the village had two main jobs to chose from, in addition to farming. There was the Swan, Ratcliffe brickworks at Hopton, and quarries at Hoe Grange, Longcliffe and Grange Mill, all served by the Cromford and High Peak Railway. By 1962 there were still twenty-three working in the quarries and sixteen at the brickworks, though much of the railway's trade had been transferred to road - nineteen of the villagers were lorry drivers. There were still forty-eight working on farms in 1962. By 1980 there were twenty-four working the farms, about thirty lorry drivers and twenty quarrymen. The brickworks had closed in 1971, the railway in 1976. In place of Oulsnam's timber yard was Robinson's steel fabrication works, employing twelve people.

While the post-mediaeval pattern lasted, while there was work in or near the village, while there were still men farming a few acres and while most of the necessities of life could still be bought in village shops, many of the old institutions survived. For more than half of the 20th century Brassington had cricket and football teams, a brass band, three chapels, the Oddfellows and the Royal Antediluvian Order of Buffaloes. After the shock of the war of 1914-1918, during which Brassington suffered along with the rest of the country, with fifteen of its men killed, the villagers resumed a vigorous social life. For forty years, between 1919 and 1959, the Brassington Reading and Recreation Society met in the 1832 school building on Hillside, run by an elected committee, usually chaired by the vicar. There were secretary and treasurer and proper minutes were kept of the committee's decisions. Subscriptions were 2/6d a quarter, soon rising to 3/- ... The subscriptions paid for repairs, decoration and glazing "the windows in the top room". There were times when the room was closed for lack of funds, but they were few and this was a strong and popular social club for the men of the village.

There were dances and whist drives in the school, which had the large room divided by a hinged screen which was common in 19th century schools. With the screen pulled back the village had a hall where they could dance to the music of the Tudor Band, the Windsor Band, John Spencer's band, Tim Wray's band. In a typical year there were dances on Easter Monday, April 23rd, Whit Monday, June 18th, July 16th, August 2nd, on September 1st and 2nd in Wakes Week, and on December 27th and New Year's Eve. These events, and the annual carnival and Wakes Week, were being organised after the Second World War by the Village Hall Committee, with the intention of raising money to buy enough land to build a new village hall. In 1948 they had reached agreement with Ashbourne Council to buy a piece of ground at the north of the Council estate for £100. The village in fact had to wait for its hall until 1982. The postwar effort raised about £1000, and a new committee, formed in 1972, had raised another £5000 in time to profit from the closure of the Congregational chapel in 1977. With the help of a local authority grant the old chapel was transmogrified and became the village hall five years later .

The Congregational chapel's failure in 1977 was followed by the closure of the Primitive Methodist chapel in 1985. Both had flourished for the first half of the century. Until the 1950s the Primitive Methodists had a Sunday School with about twenty children on the register and four regular teachers. For the whole of the inter-war period the collection at the Sunday evening service was around 15/-, rising to £1 during the war, implying a regular congregation of twenty to thirty. By the time the Hillside chapel celebrated its one hundred and fiftieth anniversary in 1984, the congregation had almost disappeared, the evangelical force of methodism spent. A similar decline has affected the third chapel in the village, the Wesleyan Reform at West End, still functioning, though with a very small congregation [it has since closed]. The decline in chapel-going has been part of a general retreat of organised religion from the centre of the villagers' lives and the older church, too, is much contracted from the days when it was vigorous enough for Brassington to be made a separate parish after centuries of being part of Bradbourne. The villagers still get married in the old church, still take their babies to be christened there and, until recently, were still buried in the churchyard -a new burial ground has now been opened at West End. The congregation, however, is too small to require the undivided attention of the vicar, who ministers to Bradbourne and Ballidon, as well as Brassington ...

The cricket team, playing on barely-suitable pitches at Wash Hills, Harborough and Longcliffe, had existed at least as early as 1862. A newspaper report on a match played between Brassington and Alderwasley in that year is reprinted in the 1967 village history, which goes on to give the results of matches played between 1919 and 1938. The team's scores were usually low, especially on their own rough pitches, making the 114 for 5 reached in 1927 against Youlgreave a triumph - the wicket cannot have been any better than usual as Youlgreave managed only five runs. That the village had good players in the inter-war years is apparent from such scores as the 129 on the Rolls Royce ground in 1934 (W. Brindley 59, E. Brittain 52 not out). Ted Brittain ... was an all- rounder at cricket (5 for 15 against Mayfield in 1939), a fine footballer , and gave a start of twenty points to the next-best player in the billiard handicaps. The cricket club was more than a team of cricketers. They organised the Carnival in 1935 and made a profit of £30-9-6d, seventy- five percent of which was given to the Derbyshire Royal Infirmary (8). This carnival included a dance at which the music was played by the Night Hawks band at a fee of £2-15-0d and which raised £20-3-6d, plus £5-4-5d from the sale of refreshments -most of the village must have been there.

There are photographs of the cricket teams and of several 20th century football sides. The footballers played on fields at Bradbourne Lane, Kilcroft, near the Hall, the Green and at Wash Hills. They won the Ashbourne Cottage Hospital Medals by beating Ashbourne Town reserves in 1900, and the history lists a string of local honours up to 1953. The team won the Cavendish Cup in 1952, though it has to be said that the village players had some help from local stars brought into the side, and [in] 1953 .. they won the Derbyshire Medals ...

The village had had [a band] at least since the celebrations for George III's coronation in 1761, and probably for very much longer. Inter-war photographs show the bandsmen, sometimes in uniform, with peaked caps, sometimes not, leading parades through the village. They played at all the outdoor events. The Village Hall committee's accounts, for instance, show a payment to "Brassington S[ilver] Band" of £3-10-0d for playing at the Wakes in August 1946. They appear regularly thereafter for similar fees - by 1950 it had risen to £5 for the Wakes parade. The ... band, however, ... was short of bodies. It found it hard to find enough players to lead a parade or take on a concert and in 1964 amalgamated with the Wirksworth and Middleton bands to form the BMW band, practising at Wirksworth ...

Rapid rises in house prices throughout the country in the late 1900s, coupled with a fashion for country living which pushed up the prices of village houses to levels which put them outside the reach of most villagers, have produced the same effects in Brassington as in most country places. The village has its share of weekend cottages and most of its people now work outside it - there is a truly rural calm during weekdays. The working village of 1881 changed slowly but change it did. As the jobs went, so did many of the families who depended on them, and this smaller village is no longer the self-sufficient community it was up to forty years ago. It has recently lost its petrol station and one of its two remaining shops. There is now only the post office. Of all the transformations through which the village has passed in its fourteen hundred years, this century's is the most complete. In changing from a place of work to one which is valued as a pleasant place to visit or to settle in, Brassington has simply changed with the times.

The Brassington mines

largely from Paupers Venture/Childrens Fortune: the lead mines and miners of Brassington, Derbyshire. Scarthin Books, 1986; by Ron Slack

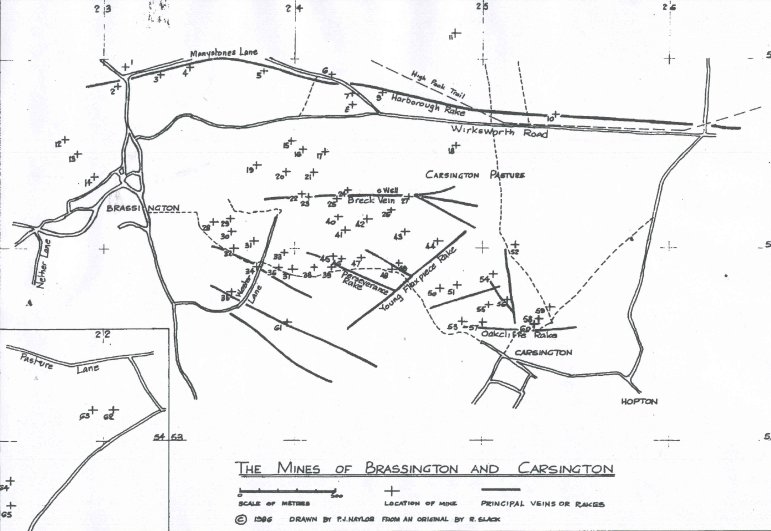

1 Wilcockstones 22 Wester Head 44 Flaxpiece

2 Longcliffdale 23 Charles Lum 45 Barisfords Pipe

3 Rider Hill 24 Hewardstone 46 Hard Hole Meer.

4 Potosi 25 Speedwell 47 Old Horse

5 Roundlow 26 Dogskin 48 Dowsithills

6 Balldmeer 27 Brett 49 Stillingtons

(Breck) Hollow

7 Upper Balldmeer 28 Corsehill 50 Old Harper

8 Pinder Taker 29 Thacker 51 Upper Harper

9 Nursary 30 Holingworth 52 Old Knowl

10 Chance 31 Lucks All 53 Old Townhead

11 Golconda 32 Nickalum 54 Innocent

(Old Brassington)

12 Smeadow 33 Perseverance 55 Butchers Coe

(in Wester)

13 Bunting Camp 34 Larks Venture 56 Childrens Fortune

14 Garden End 35 Waynes Dream 57 New Townhead

15 Providence 36 Victoria/ 58 Have-at-all

(Harborough Walk) Prince Albert

16 Bee Nest 37 Ann Gell 59 Nursary End

17 Swallownest/ 38 Perseverance 60 Cow and calf

Rushy Cliff (Carsington Pasture)

18 Condway 39 White Rake 61 Great Rake

19 Job 40 Water Holes 62 Upperfield

20 Sprint 41 Sing-a-bed 63 Green Linnets

21 Providence 42 Swang 64 Suckstone

(Picking Pitts Gate) 43 Old Wall 65 Paupers Venture

Gazetteer

This is a list of sixty-six of the mines whose location, precise or approximate, is given in surviving mining records. They include many on Carsington Pasture which have been surveyed in recent years by the Wirksworth Mines Research Group. The map references are to the current Ordnance Survey, and refer to the main shaft where it is known. There are descriptions of any surface remains which are still prominent or which illustrate mining practices, and descriptions of surface layout where it is extensive or unusual.

There are many more mines than those listed here, which have not been identified. They include many with deep, well-constructed and preserved shafts and some with surface remains.

The mines are all on private property and, like lead mines everywhere, are extremely dangerous. Many of them can be seen from signposted public footpaths, but closer exploration should be under the auspices of a recognised mining society, such as the Peak District Mines Historical Society or the Wirksworth Mines Research Group. Information about both of these can be obtained from the Peak Mining Museum, at the Grand Pavilion, Matlock Bath.

Ann Gell 2400-5390.

Barisfords Pipe 2421-5396.

Balldmeer 2419-5490.

Beenest 2403-5452. This mine's workings have been destroyed by silica sand quarrying. It was worked for barytes during the 20th century and there remain part of the metal winding gear and a diesel engine.

Breck Hollow 2460-5427. Inside a boundary wall, now almost levelled, are two buildings with a shaft between them [now filled in]. One, with walls now about one foot high, has a tree growing at one end and a shaft in the middle. The other building was the main coe and has roughly-mortared walls about five feet high. This coe is unusual in having a well preserved fireplace and chimney, the latter owing its survival to its being built with mortared joints -many of these decidedly home-made buildings were of dry-stone construction. The fireplace was recently cleaned out and discovered to contain a number of mining tools, including chisels which had presumably been tempered in the fire. On each side of the fireplace is a square recess which also contained tools but which was probably also used by the miners to store more personal objects - tobacco and pipes perhaps, or even a change of clothes. Three of the corners of the coe have the recesses which the miners used to try to conceal the full amount of their ore from the Barmaster, and thereby avoid paying the full duty. Most remarkably the floor, once a couple of feet of soil and debris had been removed, was found to have been paved with slabs of polished limestone. A set of mine tools and the chain from a stowe [windlass], was found in the workings of Breck Hollow.

Bunting Camp 2286-5450.

Butchers Coe 2505-5369. This is on a vein running at right angles to the line of the Children's Fortune workings. The coe's walls remain to a height of three feet, with a climbing shaft inside them. Below Butchers Coe is a stone-built adit, or horizontal tunnel, driven into the hillside, blocked by a shaft sunk above it. This shaft also has a ruined coe and below the adit is a dished area which was probably a washing area or settling dam.

Chance 2537-5470.

Chariot 2515-5507.

Charles Lum 2407-5427 and Westerhead 2405-5430. There is a line of shafts climbing the slope by the wall dividing Wester Head from CarsingtonPasture and, where the gradient becomes less steep, a rake at right angles to it leading toward the Westerhead mines, which are marked on the Ordnance Survey 1:10,000 map. The Charles Lum coe is at the junction of the two lines. It has walls standing four feet and a climbing shaft almost hidden by an elder bush. There is a second ruined coe about twenty yards away on the upper rake. This rake runs for two hundred yards and is about six feet deep for most of its length. There are many shafts, both along the rake and over this whole area.

Children's Fortune 2513-5372. This is complex of workings marked by a line of shafts descending the hillside to Carsington. There are the remains of a coe at the top of the line and, below, a flat depression, the site of the mine's washing area.

Condway (Conway) Knowl 2485-5453.

Corsehill 2357-5414. Above the old miners' footpath to Brassington are the remains of the mine’s coe and a crushing circle in front of it, while below the path is a settling pond. The centre post of the crushing circle has gone, but some of the track stones remain. The presence of this feature is an indication that Corsehillproduced more ore than could satisfactorily be crushed by hand - it was crushed under a wheel dragged round the circle by a horse.

Dogskin 2450-5420.

Dowsithills 2450-5390.

Flaxpiece 2475-5403. There are extensive and dramatic remains stretching down the long slope to the cart track to Carsington. Flaxpiece Coe stands on a high hillock with a boundary wall. The coe walls stand about four feet and there is a shaft inside them. To one side of the coe, inside the boundary wall, is a shallow settling area. There are shafts on the upper slope of the hill and below it, on the lower slope, is another large settling area. From there stretches a line of shafts sunk into Flaxpiece Rake, with a second coe near the bottom of the hillside. The last shaft of the series is Dowsithills.

Garden End 2295-5438.

Golconda Upper 2488-5517, Lower 2465-5537. The most recently worked mine in the area, Golconda ceased production of barytes only in 1953. It was the most highly mechanised of the Brassington mines, with compressed-air haulage and drills underground, and powered winding. The winding gear has now been removed, leaving the coe, the only intact example near Brassington, and the two shafts as the remaining surface features.

Great Rake 2395-5357 (Drawing Shaft) 2405-5354 (East Shaft). This mine has the most extensive range of surviving buildings, all roofless but with most of the walls remaining. They include coes and storage buildings, one of which, from its four feet thick walls, was probably the powder magazine. Great Rake was worked until this century, and during its last hundred years had a winding engine. Parts of the wooden winding gear are now lying in and around a stone trough. The ore was dressed in this by being plunged into water in a sieve to separate the lead from the lighter waste material. The shafts are capped by the concrete-filled wheels of the winding gear, and among the debris is a metal-rimmed five inch thick gin wheel, used in crushing the ore. The massive concrete engine mountings remain, as does a winch which was used to draw waggons on the stone-paved path down the slope to the mine road which used to run from Wester Lane. At the end of the mine's life, this winch wound barytes from the mine. This steep stone path, about five feet wide, is still easily recognisable though the mine-road itself has gone. Cartridge wadding found recently in the mine proved, when it was opened out, to consist of pages from a 1902 newspaper. The three hundred and fifty feet East Shaft was a haulage shaft.

Green Linnets 2195-5416.

Hard Hole Meer 2425-5396.

Have-at-all 2528-5360.

Hewardstone 2426-5430.

Hollingworth 2366-5409.

Innocent 2505-5386.

Job 2380-5446.

Larks Venture 2380-5390.

Longcliffdale 2307-5485.

Lucks All 2377-5403.

New Townhead 2500-5360.

Nickalum (Old Brassington) 2368-5400. In the late 1850s and the 1860s Nickalum was more productive than any mine had ever been in Brassington and bought a steam engine from Great Rake. It was worked in the 20th century for barytes, and the remains of one end of the engine house and the almost flattened walls of its coe and other buildings survived until 2002. These have now been demolished and the stone removed. The capped shaft was between the engine house and the buildings and the mine site is on a hillock, with a boundary wall.

Nursary 2444-5482.

Old Harper 2476-5379. A ruined coe with a climbing shaft inside it.

Old Horse 2435-5395.

Old Knowle 2518-5401.

Old Townhead 2485-5362.

Paupers Venture 2153-5367.

Perseverance 2410-5390. The ruins of Perseverance have almost merged into the rocky landscape where the mine was sunk on the Eastern slope of the natural amphitheatre of Wester Hollow. Among the rocks can be found two shafts near the crest of the hill, one within the walls of a large coe, the rectangular stone edged hollow of a buddle, a second coe and a settling pond. The buddle is on the same level as the two shafts, between and slightly behind them. This was where the ore, after sieving had removed most of the unwanted material, was washed in a stream of water flowing down an inclined trough, leaving the heavy lead at the bottom. Waste slurry remaining after the washing processes was run into the settling pond. The one at Perseverance is below the shafts, is walled and is about thirty feet in diameter and five feet deep. Between the pond and the bottom of the mine hillock are the four feet high walls of the second coe. Perseverance is on White Rake, also known as Blackbird Rake and Engine Rake, but the workings were found during recent exploration to centre round the two shafts in a complicated warren of galleries, rather than continue the line of the rake.

Pinder Taker 2430-2475.

Potosi 2345-5495. Potosi and Roundlow were described in 1882 as "Poor men's mines, that is capable of supporting 2 or 3 working men". They were typical of most, though not all, of the Brassington mines

Providence 2398-5457.

Providence (near Picking Pitts Gate) 2410-5440. There are four shafts grouped in a roughly square arrangement, with the remains of a coe above one of them. The shafts descend to an interconnected system of workings.

Rider Hill 2330-5491.

Roundlow 2382-5493.

Rushy Cliffe (Rushy Meer) 2415-5450.

Sing-a-bed 2432-5412.

Smeadow 2280-5458.

Speedwell 2422-5426.

Sprint 2394-5440.

Stillingtons 2455-9392. This mine was sunk near the bottom of Flaxpiece Rake. There is a capped shaft inside the remains of a coe.

Suckstone 2152-5380.

Swallownest 2415-5450 (adjacent to Rushy Cliffe.

Swang 2438-5416. There are four shafts here and exploration revealed that all had been sunk into lead deposited as a "flat" -there were no veins.

Thacker 2365-5416.

Upper Balldmeer 2430-5482.

Upper Harper 2485-5380.

Upperfield 2210-5416.

Victoria (Prince Albert) 2390-5390. A highly productive mine in the late 1840s and 1850s.

Watterholes 2423-5416.

Waynes Dream 2367-5377.

Westahead 2405-5430.

White Rake 2419-5390.

Wilcockstones 2312-5495.

Yokecliffe Rake (Oakcliffe). The shafts sunk on the Yokecliffe Rake include Cow and Calf (2530-5363), Nursaryend (2535-5357), Have-at-all (2528-5360) and the New (2500-5360) and Old Townhead (2485-5362) mines. A further mine on Barmasters' maps was Burning Drake, which has not yet been located. Cow and Calf mine's coe survives, in ruins. New Townhead has one shaft in a farm stackyard, and one at the side of the path from Carsington, filled in and currently used as a rubbish tip. Yokecliffe emerges in a quarry near the Townhead mines. Here the line of the vein can be seen in the presence of calcite in the rock of the quarry face.

.

All Rights Reserved.

.

All Rights Reserved.